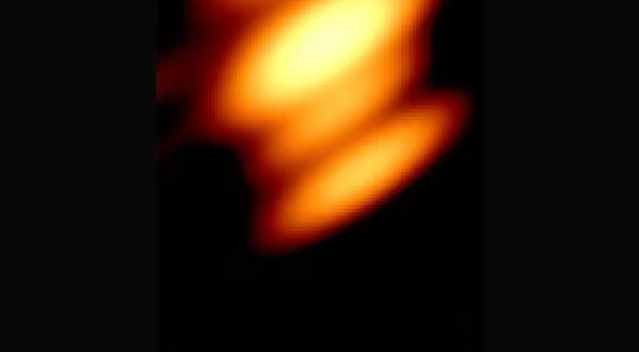

On July 3, one of the rarest atmospheric phenomena was recorded from the International Space Station-a giant sprite. The phenomenon was captured by NASA astronaut Nicole Ayers during a flyby over an area covered by powerful thunderstorm activity. The image posted on the social network caused a wide reaction both in the scientific community and among space weather observers.

Sprites are short-lived light formations in the Earth's upper atmosphere that occur at altitudes from 50 to 90 kilometers as a result of intense electrical discharges in thunderclouds. Unlike ordinary lightning, they are directed upwards, towards the ionosphere, and are branched filaments of reddish or bluish glow. It is extremely difficult to observe them from the surface of the Earth: the sprite lasts only a few milliseconds, and it appears above the level of clouds.

Satellite imagery provides a unique opportunity to capture the full structure of the phenomenon. The resulting image clearly shows how the columnar structure of the sprite extends tens of kilometers up above the lightning flashes and the light of cities. The observation was conducted at an altitude of about 400 kilometers. In terms of visual characteristics, this sprite belongs to the category of giant-it is the rarest form, characterized by a particularly bright glow and large-scale geometry.

Sprites remain one of the least studied natural phenomena in the Earth's atmosphere. Despite decades of observations, there is still no unified theory of their formation. Researchers speculate that the sprites are a response of the upper atmosphere to colossal electrical impulses emanating from powerful lightning bolts, but the exact mechanism remains a matter of debate.

Observations from the ISS, where astronauts have the opportunity to regularly capture phenomena in the upper atmosphere, are becoming an important part of the database for researchers. NASA is supporting the Spritacular project — a citizen science initiative where planetary residents and space mission participants can share photos of sprites. The goal of the program is to collect the most complete archive of images that will help you understand how, where and why these rare phenomena occur.

Astronauts working in orbit are increasingly involved in collecting such data. Many of them are fond of photography, documenting unusual natural phenomena in the Earth's atmosphere. Their images become not only a part of scientific archives, but also a tool for visual popularization of science.

Given how short and inconspicuous the sprites are for ground-based observers, such photos from orbit open a unique window into the world of rare processes occurring above the clouds. Questions about their impact on atmospheric chemistry, their relationship to space weather, and their role in Earth's global electrical system remain open. New visual data can help scientists narrow this knowledge gap.